“Inundation District” Screened for Public at Somerville Theatre

Wednesday, May, 1st, 2024 Home Slider News

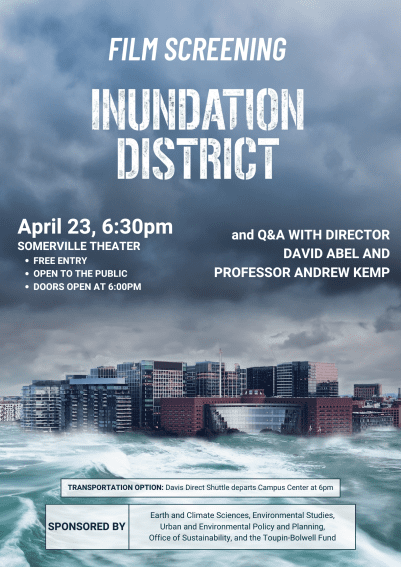

A special free screening of “Inundation District” took place for members of the Tufts community and the public at the Somerville Theatre on Tuesday, April 23. The film, directed by David Abel, explores how the City of Boston—particularly the city’s new waterfront Seaport district—is threatened by rising sea levels. The film follows the construction and extensive investment that went into building the Seaport, which Boston calls the “Innovation District.”

A special free screening of “Inundation District” took place for members of the Tufts community and the public at the Somerville Theatre on Tuesday, April 23. The film, directed by David Abel, explores how the City of Boston—particularly the city’s new waterfront Seaport district—is threatened by rising sea levels. The film follows the construction and extensive investment that went into building the Seaport, which Boston calls the “Innovation District.”

The threat of accelerating sea level rise, however, has led others to call the neighborhood the “Inundation District.” The Seaport district, which has undergone significant redevelopment in recent years, is especially susceptible to climate-related flooding. The district and nearby areas in Boston have had more high-tide flooding than any other city on the East Coast since 1980, with the threats of “king tides,” or exceptionally high tides, and storm surges raising serious concerns for the longevity of these parts of the city.

The screening was co-sponsored by the Earth and Climate Sciences, Environmental Studies, and Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning departments, as well as the Office of Sustainability and the Toupin-Bolwell fund. Many Tufts students were among the audience, which also drew in members of the surrounding Medford/Somerville community. The screening was followed by a Q&A session with Abel, who is also a reporter at The Boston Globe and a Professor of the Practice in Journalism at Boston University, and Tufts Associate Professor of Earth and Climate Sciences Andrew Kemp, who conducts research on sea level rise in the Boston area and along the East Coast.

Some attendees had questions about the possible solutions and actions that Boston could take to prevent increasing damage like flooding, storm damage, and erosion from rising sea levels. In the film, researchers discuss possible options like the construction of a sea wall along Boston’s harbor islands or smaller-scale solutions like the “Emerald Tutu,” a floating biomass-based module that can dampen wave energy.

“There are other things that are mentioned as potential solutions, and one of them is shoreline defenses, and I think that is the principal plan right now,” Abel said. “But those take time, they’re expensive, you can’t build them everywhere you need, there’s a whole lot of zoning challenges.”

Abel’s film underscores the heavy question of who will bear the expensive costs of dealing with the climate crisis and its effects on the city. “Inundation District” features interviews with both a major developer in the Seaport district and with local residents who are seeing the impacts of climate crisis first hand.

Abel’s film underscores the heavy question of who will bear the expensive costs of dealing with the climate crisis and its effects on the city. “Inundation District” features interviews with both a major developer in the Seaport district and with local residents who are seeing the impacts of climate crisis first hand.

“I think we need to raise the question about should we still be building in these areas and should we be bailing out folks, or should there be some sort of shared arrangement in which developers somehow kick in a larger disproportionate share to cover the cost of defending the development that they knew was being billed in a flood zone?” Abel said.

Professor Kemp also spoke about the major threat that Boston faces if the speed of melting ice in Antarctica increases. The film explains that Boston could experience 25% more flooding than other parts of Antarctica.

“All the US East Coast, such as Boston, would experience a sea level rise melting in Antarctica that exceeds the average,” Kemp said. “Conversely, we have less fear here in Boston for melting with the Greenland ice sheet, [when] we would only see about 70% of the global average. So, which ice sheet melts makes a real big difference to places around the world.”

The screening of “Inundation District” and director’s answers afterwards left attendees thinking about the importance of addressing the climate crisis, which is already affecting Boston.

“We have a 400-year-old city with tens of billions of dollars of real estate that is vulnerable to what we know is coming. We know the seas are going to rise even if we stopped emissions today. We know storm surge is going to increase,” Abel said. “We need to start taking action because time is running short.”